Indira Sawhney – I

The Indira Sawhney & Ors Vs Union of India – I (also known as the “Mandal judgement”) is available online in full at http://yfelegal.blogspot.com/ (Thanks to YFE)

Read it in full.

I leave you with a couple of paragraphs from the judgement

What does the expression “Backward Class of Citizens” in Article 16(4) signify and how should they be identified? This has been the singlemost difficult question tormenting this nation. The expression is not defined in the Constitution. What does it mean then?

Reality Check would like to add that the lack of an objective definition of OBCs has the potential to lay this country to waste. Yes, it is that bad. On one hand it denies equality of opportunity to hundreds of millions, on the other it makes a mockery of social justice for the truly deserving.

Today, this OBC quota policy is mired in litigation and there is no end in sight. Without a actionable definition of “backward”, how far can we go before a grand showdown ? The great T.T.Krishnamachari had predicted the impending constitutional mess.

Mr. Krishnamachari asked : “Who is a reasonable man and who is a prudent man? These are matters of litigation”.

. . in response to . .

“What is a backward community”? . . . A backward community is a community which is backward in the opinion of the Government. My honourable Friend Mr. T.T. Krishnamachari asked me whether this rule will be justiciable. It is rather difficult to give a dogmatic answer. Personally I think it would be a justiciable matter. If the local Government included in this category of reservations such a large number of seats; I think one could very well go to the Federal Court and the Supreme Court and say that the reservation is of such a magnitude that the rule regarding equality of opportunity has been destroyed and the court will then come to the conclusion whether the local Government or the State Government has acted in a reasonable and prudent manner.

See links to Indira Sawhney II here “How Kerala got its cream back“

Tamil Dravidian intellectuals and EWS anti-Brahmin spin

It never fails to amaze me how a people can so willingly reject reason and adopt the bad faith. As a group. With no outside pressure. Out of their own free will.

Have I shared this vile Anti-Brahmin cartoon from the Tamils (Dravidian) on my Twitter account?

The artist name signed in Tamil is சித்ரன் (Chitran 2.0) This cartoon is widely circulated in Tamil social media. IT shows a stereotypical fat Tamil brahmin drinking from a large class which is already full while the skinner and smaller OBC are made to share a much smaller class which is nearly empty and the TBrahmin is also stealing from this meager. A complete LIE and the exact opposite has been the case in Tamilnadu. You can see the similarity of the Tamil language propaganda to the Nazi lies and canards against Jews. You have to notice closely, this is NOT a casual drawing, everything is carefully placed. This cartoon however is stolen from Chinese propaganda – repurposed to Dravidian Anti-Brahmin propaganda artwork.

EWS videos use this image and spread misinformation

One of the striking things that outsiders do not know about Tamil is the insane amount of engagement on social media. A 2L sub channel is average. I hoped someone would come forward to document the proliferation of Dravidian channels, maybe I will do it myself. In any case, Kulukkai is a 2.3Lakh Subscriber very popular Dravidian channel in Tamilnadu with over 35 Million views. Read my post “DO not trust any ally who claims this is fringe”.

After the EWS case was lost Dravidians and their allies the Idea of India ecosystem in Delhi have gone into overdrive to build a campaign to launch attacks against the judgment. You can notice pieces in Indian Express, Hindustan Times, The Hindu and others.

Dravidians launched three new books in an event recently. The YouTube videos features Mr P. Wilson DMK MP and Mr G. Karunanidy the AIOBC Federation. The videos can be seen on Kulukkai https://www.youtube.com/@kulukkai/videos

You can notice the cartoon used in the propaganda material. New Delhi lawyers do not understand Tamil hence they dont see this side of the Dravidian Janus face.

Their idea of Social Justice is not what they tell you in English. If India were smart enough to even ask them in the first place.

This G. Karunanidhi clearly exposes his Dravidian version when “Social Justice” was achieved in the first 100% Non Brahmin assembly. This shows the mindset of the highest level of Tamil (D) intellectuals. This is their vision. It isnt about Savarna vs Dalit vs Bahujan etc. I see many Savarnas ministers in the picture below.

I do not even think the Dravidians lost the OBC case. They got by without the Supreme Court touching upon ANY of the key issues. The loss is merely Technical. It is quite possible the judges merely are not that sharp to search and spot the intrigues.

The speeches

- Show the depth of the Dravidian braintrust. They show a deep knowledge of Indira Sawhney, Thakur, and other judgments

- Demonstrate great passion while delivering the oration

- Shows their great energy designing and challenging Laws at the national level. In the Parliament when they had power , unlike the BJP.

- Show expert deftness in dancing very close to the danger line – eg while saying Reservation is about representation – yet avoiding examining the representation in Tamilnadu. This shows the eagerness with which deception and badfaith is embraced.

- Isolating the Brahmins in true Tamil (NonBrahmin/Dravidian) intellectual style. GK says in Tamil “they 76 castes will get benefit of EWS, but trust me they will not get anything. This 10% is only for Brahmins”. Suggesting they will be pushed out.

- Using anti-Brahmin Tamil language cards for YouTube content the images above say in Tamil (P.Wilson) “Conspiracy to destroy reservation. This is the Beginning” (G.Karunanidhy) “Brahmins mete out injustice in the name of the poor“

- Using techniques of expanding scope fallacy. Look at Chief Secys in Delhi – they are all Brahmins. If not Upper Castes. Why look at Delhi? Lets look at Chennai.

- The DMK lawyers against EWS are said to have opened with the Ekalavya story. This type of strategy takes the issue OUT of the plane of rational and contemporary social analysis. Who is the descendant of Eka today? It isnt a “thing” it is an “emotion”. A poorly trained bench can never match this level of determined and planned challenge.

The essential question is “Who will ask these questions”

I see the BJP frightened and the Supreme Court delinquent.

It is about Tamilnadu stupid ! A no bull guide to the EWS judgment

I am going to eschew verbosity and legalese here to present a ‘no bull’ raw view of the issues around the 103rd constitutional amendment. This amendment enabled states to provide reservation up to 10% for the ‘poor among the forward castes’. On Nov 7 2022 the Supreme Court of India ruled in a majority verdict 3-2 to uphold the constitutional amendment.

You can read longer pieces written by me on the matter at “The EWS Quota wrench in the Idea of India process” and “Is the EWS 103rd Amend a constitutional fraud”

Ok first – as promised let first cut the BS. This is not a quota for poor. It is a quota for castes that are not included in any of the reservation categories (SC / ST/ OBC) In other words , the ‘unreserved castes or the forward castes”. The income limit is merely shiny new creamy layer filter for the new quota.

Is a Quota for the hitherto unreserved castes desirable ?

I have been against economic reservation for a long time with the logic “Why should I give my medical seat to you because my dad owns a car ?” Life is about fighting odds. However, that is not the case here. We have a more fundamental problem – the intractability of bringing the OBC quota regime under monitoring. During debates of the First Amendment Ambedkar guaranteed that the Court would scrunitize runaway mischief in classification of castes as “backward”. However that has not happened. During the 2007 OBC quota case Thakur the court with great bombast said that there would a review of castes after “5 or 10 yrs”. That time has come and gone – there has been nothing.

The EWS reservation is nothing but a legislative response to a grand dereliction on the part of the Supreme Court.

Tamilnadu “Dravidian” model is the reason

First of all a capable Supreme Court bench would have started with the most fundamental of questions – What is the necessity to have an EWS quota – if castes X/Y/Z are left behind the automatic checks and balances in the primary OBC quota mechanism would kick in and ensure they are included in the OBC regime. Think hard. Think. This is the level at which Dravidian ideology operates.

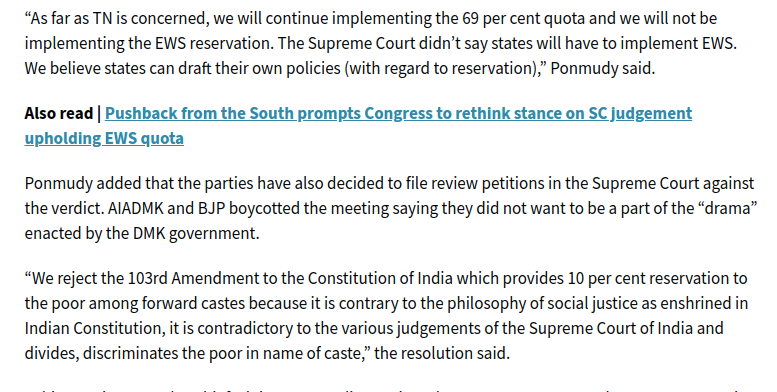

Tamilnadu is the state that necessitated the EWS quota in the first place. and it is also the state that is leading the most vigorous opposition to this quota. Almost all states have notified the 10% quota as a matter of search for equilibrium – except Tamilnadu.

Vacuous yet loaded statements like “it is against the philosophy of social justice” should invite curious minds to inquire Tamilnadu. Is Dravidian Anti-Brahmin the philosophy of social justice ?

Tamilnadu specifically the DMK is the primary mover against the EWS reservation. Why is Dravidian movement so inconsolable?

Read on.

Exclusion forms the basis of Tamilnadu reservation

Tamilnadu’s uniqueness is not merely that 69% of seats are reserved or that creamy layer is not excluded which allows multiple generation families to avail the quota. What is unique is that 97% of the population is classified as backward (See my post on NSSO Statistics Handbook showing Demographic data of Tamilnadu) . This is egregious and flies in the face of Supreme Court observations in Indira Sawhney that reservation for all is reservation for none.

But what is missed is the Anti-Brahmin imperative – reservation for all but Tamizh Brahmins is nothing but invidious discrimination against Tamizh Brahmins. This is running unchecked even in this case which resulting in defeat for Dravidians.

I know people would argue that other Tamilnadu castes like Nattukottai Chettiars ( P Chidambaram), Saiva Arcot Vellalas (PTR Palanivel Rajan), Balija Naidus are also impacted but the numbers do not support that. Perhaps they use a cognate caste, perhaps only Tamil Brahmins are face controlled. Regardless, the total absence of support from these community leaders who form the DMK/DK leadership such as Suba Veerapandian, Palanivel Thiagarajan betrays there is something more than meets the eye.

Idea of India jurisprudence accommodation of Dravidian ideology

Tamilnadu was able to get away for 17 years with flouting the basics of Indira Sawhney in both the depth 69% and the width 95% inclusion. Every year the Supreme Court pampered this violation with an extension as they deferred examining the Tamilnadu Reservation Act of 1994 from one year to the next with some spurious bandaid formula. In 2011, after 17 yrs the Supreme Court while disposing all challenges demanded the Tamilnadu Govt to collect quantifiable data to justify its case. For its part the Tamilnadu Govt constituted the Janarthanam Commission which essentially told the Supreme Court what amounts to mind its own business. See “Perpetuating the scourge of caste – P. Radhakrishnan of MIDS”

Why cant Dravidians just give the 3% and gain impenetrable armor?

This is an absolute cardinal question curious minds in New Delhi must ask the Dravidian-Tamil when they present objections.

Lets cut the BS, every caste gets included in Tamilnadu. In that case, Dravidians can give 3% – not 10% and set a limit of 5 Lakhs and be done with it. You would think this is the rational thing to do for a democratic party. Imagine this would seal the mouths of their detractors for good. They certainly are not averse to such quotas – DMK announced 3.5% for Christians (later withdrawn due to communities own rejection) and 3.5% for Muslims. Imagine the peace and unassailable armour it would give the Dravidian ideology. If you do not understand this – you will not be able to understand the deafening noise and why Tamilnadu wants to remove the EWS as a concept itself. Even from other states and centre.

Ready ?

Two reasons why Tamilnadu cannot give the EWS quota.

- Brahmins will come inside – in Tamil பாப்பான் உள்ள வந்துடுவான் – if TamizhBrahmins are given representation the the central weapon of Dravidian activism – the nonstop invective and hate propaganda has no meaning at all. The whole point is to keep a hostile environment alive and slowly remove the Tamil Brahmins from spheres of influence.

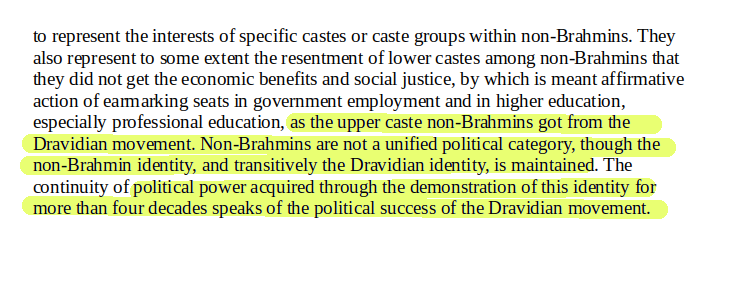

- Turns focus Inward. This is even more important than the first. Remember in Tamilnadu the OBC lists are completely opaque, data about individual communities who dominate the lists are kept as the highest level of state secret. Even the Supreme Court is unable or unwilling or cowardly to extract this most basic check (supra). The Dravidian ideology need the Tamil Brahmins to be outside. As long as the Dravidian movement has the “Oustide” to direct energy against they can keep the “Inside” list away from scrutiny. Imagine if Brahmin get their 3% – then there is hardly any point left to abusing them any longer. Hence the public attention will turn INSIDE and pressure for revealing data will instantly shoot up. This will end the “Non Brahmin” collective and transitively the Dravidian ‘movement itself.

As Prof E. Annamalai has explained beautifully the spectacular longevity and political success of the Dravidian movement depends on maintaining the “Non Brahmin” as a unit. The main tool to maintain the “Non Brahmin” is virulent Anti-Tamil-Brahmin saturation propaganda. Today this propaganda dominates Tamil social media like Twitter and YouTube.

Top 6 – spurious and petty arguments from Drav-Tamils on EWS

Here is a list of petty arguments put forth by Tamils (Dravidian bent) which have been swallowed by the less curious and less capable Congress party itself. It is a testament to the Supreme Court judges abilities that such petty stratagems have not been shredded and shown their place.

Reservation is not a poverty alleviation scheme

It isn’t an unjust enrichment scheme either.

Social justice is about representation

Awesome. Then the entire scheme has to be based on representation data. Lets start with Tamilnadu PG Medical data for instance. This is the high echelon goods. Lets see the breakup data by caste.

EWS is against the philosophy of social justice

What is the philosophy of social justice in concrete terms.

Philosophy of social justice is to help historically oppressed castes not Brahmins

How can 97% of Tamilnadu be historically oppressed ? See here it is quacking like a duck and walking like a duck. Hence it is merely a way to enforce an Tamil Brahmin exclusion based on anti-Semitic logic.

103 Amendment excludes poor among OBC

A contradictory claim from the likes of Karti Chidambaram (A Chettiar who is assumed to be in Forward caste list) this also forms the minority dissent of the two judges. Firstly, If reservation is not a poverty alleviation scheme why do you care about poor among OBC? Crocodile tears. Secondly, we are discussing a constitution amendment to enable unreserved castes there is nothing that prevents Tamilians from introducing a 10% sub-quota within the OBC 50% (BC+Muslim+MBC) for poor among the non Brahmins.

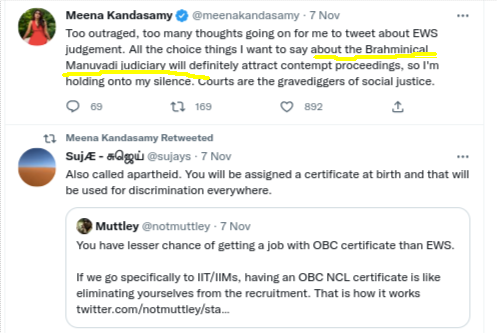

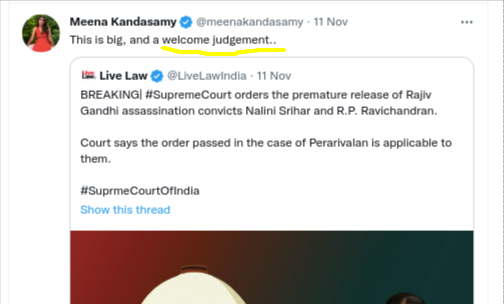

All judges are Brahmins

Then why do Tamil-Dravidians who claim to represent all Tamil Non-Brahmins even bother with the court arguments and judgement contents ? Is it to demonstrate that Dravidians are immune from contempt laws. Do you people want a reasonable debate with Anti-Semitic like outlook. How come you people welcomed the same Manuwadi Brahminical judiciary for releasing all of Rajiv Gandhi and 16 others assassins?

the same Brahmins judiciary

We have problem with 8Lakhs income limit the “அரிய வகை ஏழைகள்” rare type of poor people ?

Hmm, in that case you Dravidian-Tamils would have litigated the income criteria. Hence this is a merely a Tequiyyah (an Evil lie) a stratagem. Kerala income limit is 4Lakhs – they are still alive.

These EWS cartoons made by Dravidian-Tamils prove the real nature of people like RCI

Sweet Chellam..!! See how you people have reduced the debate to its bare elements. That is how I like it. Bare faced.

What next

The plan would be to activate the Idea of India ecosystem journalists and lawyer assets and build up a corpus of articles in mainstream media. Then follow up with a review petition. I notice they have already tied up with a constitutional level expert lawyer.

As shown above implementing EWS in Tamilnadu has the potential of ending the Dravidian movement. Hence the extreme noise. All other states have seen the moral argument “If every other caste has a share the judiciary isnt doing its job then I see nothing wrong in a safety net for unreserved?” This simple reasoning cannot be absorbed by Dravidian Tamils because it defeats one of the key imperatives of the Dravidian movement itself. An Anti-Semitic like urge to expel.

On OBC reservation policy in medical education

A major development took place in Madras High Court on Friday June 19, 2020 when the Union Govt filed an affidavit agreeing to OBC reservation for admission to MBBS/PG Medical seats in the “All India Quota”. A lot of misreporting is happening in the mainstream media. Look at these two conflicting reports :

OBC quota in medical seats only in central institutions: Govt informs HC (Hindustan Times)

Centre says it is in favour of OBC quota in medical seats (The Hindu)

So which one is it? I will try to explain the matter in simple terms in this article. This issue is of monumental importance because Post Graduate Medical Studies is the highest echelon professional education degree you can aspire for in this country.

Writing on the reservation policies can be confusing because there are three parts to it. The facts – you need to know how it operates regardless of whether it is desirable or not, how the beneficiaries are selected, qualifications, rules, etc. The core principles – the first principles involved, the anomalies, the judicial failures, the contentious issues regarding equality, the boundary conditions, intra group issues, the merit arguments. The political ramifications – how politics can congeal around these citizenship classes, inside vs outside groups, alliance building where each group works to secure its gains, how the media mischief works. I’ve read far too many articles about the reservation system where these are mixed up and end up in an incoherent jumble. So lets begin.

The facts

How are doctors made in India, how many seats ?

I am going to leave out Dental, AYUSH (natural), and Veterinary — sorry guys!. Just to keep it simple and use round numbers.

There are about 80,000 MBBS (undergraduate) seats and 30,000 MD (post graduate) seats. The post graduate medical includes surgical MS and clinical MD and Diplomas. These distinctions are not important.

The key point : The PG degree is seen as a must have for MBBS doctors. You can see there is a giant funnel gate right there. Of the 80,000 doctors only 30,000 will go on to get a PG degree. The competition is hence fierce and the professional rewards are high. “MBBS doctor” is seen as a different brand.

How is the capacity distribution ,state, centre, private?

Most of the capacity is with the states roughly in 90:10 ratio. For undergraduate: The central govt medical colleges with capacity are the 15 AIIMS which have roughly 1000 seats put together, then the “Delhi and Union Territory colleges” come up with another 500. This is the same for PG as well.

In the state capacity, the states have govt colleges, private non-minority, and private-minority colleges. The government capacity is very affordable and is highly sought after the private colleges are super expensive and have an elaborate cross-subsidy scheme. They surrender a small portion to the govt at a discount and compensate for the tuition loss by charging hefty tuition in the private quotas.

The south has a much higher state govt as well as private capacity. The private capacity is a money spinner a lot of politicians are players in this domain and there are lot of business monopoly games guarded by a complicated and arbitrary NOC/ EC (Essentiality, No Objection) process. This provides these players to extract a monopoly price from this demand. The very small batch sizes 50, 100 intake in UG makes private medical even more expensive. The north-south gap is closing but this is the current lay of the land.

What is this All India quota business ?

To offset the regional imbalances – the central govt instituted an All India Quota in both UG and PG capacity. Per this rule 15% of UG seats and 50% of PG seats are taken from the states and filled using a common merit list. This allows ANY state candidate to apply to these seats.

Timeline:

- 1984 : First broached idea of All India Quota at 25% (Dr Pradeep Jain case )

- 2003 : PG quota for AIQ increased to 50% (Saurabh Chowdhry – CJI Khare time a TMA Pai judge)

- 2007 : 22.% quota for SC/ST within the 50% AIQ (Abhay Nath)

Is this related to NEET?

No this is not related to NEET. Even prior to NEET the AIQ existed – the common exam used to be called AIPMT (for both UG and PG).

What is the reservation policy – it is too confusing ?

The All India Quota fills two capacities —

- seats in central govt controlled institutions (AIIMS, PGIMER, Maulana Azad etc)

- seats taken from each state using the 15% UG/ 50% PG formula.

In (1) the central institutions the standard central govt reservation scheme is followed – same as IITs. This breakup is : 15% SC/ 7.5% ST/ 27% OBC and now 10% FC-EWS , 40% Open Competition. CHECK. No Problem here.

In (2), only the SC/ST is followed. The breakup is : 15% SC/ 7.5% ST 77.5% Open Competition. Problem here.

In the PG level there are roughly 1,000 seats in (1) and 10,000 seats in (2). Now let me introduce the issue.

The OBC organizations demand that in (2) the 27% OBC reservations be imposed.

Can you simplify this further ?

To simplify remove the UG from the contention due to the fact that only 15% is in this category and there is no funnel-gate. Only focus on the PG capacity to zoom in on the crux.

In the 10,000 seats in the All India Quota for PG seats. The demand is to have OBC reservation and shape that along the usual formula (SC/ST/OBC/EWS/Open)

What happened in court in past week ?

The OBC organizations and the Tamilnadu parties filed a petition in the Supreme Court on May 29 2020 demanding that the ongoing admissions to PG Medical Courses be stopped and 27% OBC reservation be applied. (link credit Bar And Bench). This was dismissed on the ground that only Fundamental Rights violations can be taken directly to the Supreme Court , the judges held this was not a fundamental rights case and tossed it to Madras High Court. The parties immediately filed in the Madras High Court. During the hearing the Central Govt Health Ministry filed an affidavit declaring that they are in favour of extending the 27% OBC quota in all seats and that they had filed a similar affidavit in another case already pending in Supreme Court since 2015 in a Writ Petition Saloni Kumari and Onr.

So the issue is back in the Supreme Court where the aforementioned Writ Petition is scheduled to be heard on July 7 2020.

What about the caveat about the overall 50% limit and existing seats cant be disturbed?

I would not think too much about it. This shows that neither the govt nor the judiciary has a “core” level insight into the issues involved. In the Indian framework , what they do is keep the current capacity as-is and add extra capacity to one one group then declare that “why are you bothered? the number of seats are the same for you”. Just a sweetener.

Moreover, the 50% is incorrect, because the new limit is 60% after the FC-EWS quota.

The Tamilnadu sides want immediate imposition of the OBC quota by expelling the 27% unreserved doctors and carving out an exclusive quota. This is as per the scheme of things and a valid demand. The Affidavit declares a rule that the absolute number of seats currently available to the Unreserved (again this is Open competition available for OBC doctors as well) must not be reduced. This means the states have to cough up extra capacity by creating more PG Medical seats for OBC alone. I dont see a huge problem with this – after all these are just MCI rules which dictate the seat capacity. That can be tweaked.

So what is the current situation for this year ?

The govt cited the COVID-19 crisis to claim that disrupting the 2020 PG Medical seats will cause suffering hence it appears that this year PG medical seats may be filled without OBC/EWS reservation. Second, breaking the promise and expelling the general category students AFTER the game is played will be an egregious violation of fundamental rights. Maybe too much even for a “transformative progressive” court.

Part 2 : Core Principles at play

Now lets move to the Core3 topics, these are more fundamental and not linked the legal matters. It is very important we have a proper grip at this level. I dont see this either in the judiciary, government, or any of the think tanks.

What are the reservation dynamics of PG Medical in particular ?

Indian reservation policies are not applied at the level of the degree rather at the micro level at each site. As mentioned, PG Medical is the holy grail of professional education in India. But some specialties in particular are in very high demand – for example M.D. Radiology is the creme, M.D. Dermat is second and so forth. The 27% reservation does not mean 27% of PG seats will go to a group but that 27% of M.D. Radiology in College Hospital X will go to OBC doctors. Each discipline in each college-hospital is divvied up.

Is it true that only 250 OBC got admission in AIQ ?

False. You need to understand that in the 77.5% existing Open Competition all groups can compete. In NEET PG 2018 I have the following numbers : Of the 10,400 seats 2,500 were taken by OBC. Of the 1000 odd seats in AIIMS/Delhi Colleges 257 were taken by OBC in the “OBC quota”. The OBC activists never count the OBC doctors who were admitted in the open competition. When they say “2800 seats denied to OBC” they mean “over and above” the 2500 they got in the open competition. The keyword “Over and Above” was first used by Marc Galanter to describe the Indian Vertical Quota system. See Reference [1] for full list of 2018 AIQ PG Medical seats allotment.

What do you think of the reservation jurisprudence ?

On all #core items, Indian “transformative constitution” jurisprudence comes up a cropper. Very poorly developed tests, incorrect framing of questions, freely adopting spurious arguments, temporizing, inconsistency, sectarianism, grandstanding are in display. For example : Why did the Supreme Court not mention the Saloni 2015 writ petition when dismissing the May 29 case? If reservation was not a fundamental right , why admit the Saloni 2015 petition in SC? Most importantly, this is a wide impact issue affecting how Doctors are made in all of India. How can you keep such a crucial case pending from 2015? It is very important that a major injection of #core is required in these institutions. Our public intellectuals come up woefully short too. Otherwise these anomalies build up and when they crumble at some later date it will a very painful experience for all of us and our kids.

What is the underlying issue with Tamilnadu and OBC?

Tamilnadu is the epicentre of all this action. Why? This is a very important issue that others may not get. In TN, almost everyone 93% to 96% are in reserved category. Roughly 74% are in OBC category (NEET TN 2017-18). This is not the case with any other state. The bald truth is – Tamilnadu reservation categories are designed to exclude the Tamil Brahmins. Nothing else explains the ratio of applicants to MBBS. The other forward castes are likely using a synonym.

Back to the PG issue. I have data from 2018 Tamilnadu state quota of 50%. This is the part where each state applies its own reservation policies on its doctors.

- Of the 1272 PG Medical seats – FC 53, BC-Muslim 63, MBC 318, BC 604, SC 199, SC-Arunthathiyar 33. [Reference 2]

- Only 53 MBBS doctors are from unreserved castes out of 1272 !! Even though the total number of unreserved seats are 394.

This shows that the BC group in Tamilnadu is fully competent and capable and most likely includes forward castes in the mix. The top 30 ranks are OBCs.

Futhermore the Tamilnadu OBC group is divided into the MBC which is a more accurate social justice group. When you collapse to an All India Quota, the MBC group do not get the spots. This only works as a ‘lets get a foot in the door first’ tactic.

The central problem with extending OBC quota to the AIQ list is : it will impact states with OBC doctors who might represent really backward classes, measured using a capabilities test. You should be able to foresee the pressure and pull that will be created if you release such a large OBC doctor contingent from one state.

Are doctors educationally backward ? The limits of reservation entitlement

The Tamilnadu MBBS doctors go through the same courses, live in the same hostel, have the same facilities, then earn well. SC can be said to have suffered from systematic issues, but certainly not the OBCs. I cant imagine how these high specialty courses like M.D Radiology , Anesthesia, will be out of reach of OBC MBBS doctors if they compete with all. Also the creamy layer issue is a joke. The MBBS doctors income is not considered and his/her parents income too from salaries/agri. Very few doctors will fail to qualify for NCL (Non Creamy Layer) certificate. I dislike the creamy layer concept itself. A poor quality judicial invention , a sweetener of the Indira Sawhney (Mandal) era.

Part 3 : The political part

Who is claiming credit ?

None of the parties are coming out of this looking good. The DMK never bothered about this for 14 years ! But once they seized of the matter they moved at a rapid pace. Credit must be given to P.Wilson Advocate and MP.

The BJP govt has filed an affidavit agreeing to this reservation from 2015 but is not stepping up to take credit. They seem like a deer caught in headlights. This lack of confidence is due to not understanding the issue at a core level. The courts are not looking good because who would temporize such a crucial case for 5 years !!

What about the political economy dynamics ?

I group all reservation / social justice matters as #core3. The central idea in all of these case is DATA and SCRUTINY. The court’s central duty is to guard and insist on data otherwise factional politics will drive the country into a low grade democracy. Only a tiny swing group, I call Free Agent voters will really vote on public or national interest matters. In Tamilnadu case, both 71 Sattanathan commission and 82 Justice Ambasankar commission clearly warned that a handful of castes are lopping up the benefits. This will hold true today as well, these winning groups will stick to the political formation that perpetuate these benefits and prevent a study. That is the rational behavior, you cant grudge anyone for that.

So what is your recommendation ?

In all #core3 issue data must be a prerequisite. This must be non-negotiable because ignoring this will exponentially increase the costs of this data becoming public in future. This will lead to violence because it is one thing if chips fall unevenly in open competition but if social engineering results in uneven benefits, people will react.

This is a golden rule that must be followed at a minimum. Whenever you extend reservations into a new frontier, you must insist on a data checkpoint. As I mentioned the OBC Doctors already crossover 25% into the open category. So further reservation for PG does not pass the sanity checks. The irony is something as simple as college admissions to make doctors need a battalion of lawyers, dozens of court cases, supreme court benches. Something must be wrong. No other country has this feature.

The unreserved castes are somewhat protected by the new 10% EWS quota which is a counter weight. Reservation on economic group is like adopting a HORRIBLE idea to offset a BAD idea.

This is a clear sign we are in a race to the bottom.

References :

- NEET PG 2018 Medical All India Quota counseling round 1 results. Pull this into Excel and you can see that OBC won 2500 odd seats. The activists do not count this. 2018 PDF All India Quota Allotment including Central Institutons aiq

- NEET PG 2018 Tamilnadu 50% allotment. Again pull into Excel and count the number of each category. Out of 1272 seats only about 55 are taken by Unreserved candidates. pg-medical-phase-one Tamilnadu PG Medical 2018 allotment

- Common Counter Affidavit filed by Union Health Minister agreeing to provide OBC quota for PG Medical , perhaps from next year onwards Credit to Bar and Bench for the PDF, I had to save a copy on my blog only because links tend to vanish over time) Common_Counter_affidavit_of_R_4_in__W_P_No__8326_of_2020__8324_of_2020___batch_

The EWS quota wrench in the Idea of India process

In 2019, the Narendra Modi govt announced a 10% quota for “EWS – Economically weaker sections” by passing the 103rd Constitution Amendment which introduced Art 15(6) education and Art 16(6) jobs into the Indian constitution.

‘15(6) Nothing in this article or sub-clause (g) of clause (1) of article 19 or clause (2) of article 29 shall prevent the State from making,— (a) any special provision for the advancement of any economically weaker sections of citizens other than the classes mentioned in clauses (4) and (5);

In my view, this is the standout accomplishment of Narendra Modi’s first term because it is addressing a core agenda item no 3. Like all core items, these may not create noise but permanently disrupt the earlier idea of India equilibrium. Several controversies have arisen in the wake of this EWS quota. Here I try to answer them in a Q&A format rather than a long winded essay. I believe it is the right format because the questions are as important as the answers to them.

Q1. Why are people opposing quota for all poor , since this is poor from Open Category?

Lets get this common misconception out of the way. The 10% EWS quota announced is only for those NOT covered under reservation. Only those castes who are disqualified from availing OBC, SC,or ST status would be eligible.

On the other hand, since there is no list of Forward castes , in theory anyone can reject their birth caste group and avail of this quota instead. In practice however, this may not make unless there is advantage of doing this.

Q2. It is unconstitutional to give EWS quota

A common strategem of Idea of India groups against #core3 is Justice O Chinnappa Reddy’s famous observation during Indira Sawhney case – ‘reservation is not a poverty elimination program‘ . Dravidian ideologues like the erudite Prof Suba Veerapandian have latched on to this for years justifying the inclusion of the creamy layer in Tamilnadu. This has denied benefits to millions of poor OBCs while enriching the already advanced groups. The correct response to this is :

While it may be true that reservation is not a poverty reduction program, it certainly does not mean ‘reservation is an unjust enrichment program‘.

The Supreme Court is about to start hearing petitions challenging the constitutional validity of the 103rd Constitution Amend starting July 16 2019. But keep in mind , this is a not a review of a law against the existing provisions of the constitution. They are not bound by the usual core3 cases like Thakur (2007), Sawhney (1992), MR Balaji (1962). The upcoming judicial review will be a basic structure test. Think about it, if the Supreme Court were to strike down the 103rd Amend it would be in effect be saying “Helping the poor of the general category is against the basic structure of the constitution” !! This is an extremely bizarre position and would require significant literal obfuscation by the ecosystem to make palatable. The expansion of #core elements across India will make this task much more difficult.

Q3. Do you support EWS quota ?

No. It is crazy. I have already stated during the RTE case , EWS quota gives a permanent benefit on what is a temporary disadvantage. Peoples fortunes change all the time. You cant put a checkpoint at a particular instant and then give a permanent benefit based on that. This is especially true of high echelon goods like MBBS admissions. It is unacceptable that a student has to give up his MBBS seat which determines his entire life trajectory just because his dad committed a crime of owning a flat, or succeeded in a job.

But .. but.. but.. there is a gotcha.. see next question.

Q4. So you dont support EWS, so why are you jumping ?

Well core analysis always look at the entirety of the picture and not unbundle and then pick and choose. There are two issues in the current reservation regime which makes EWS a necessary check.

- The startling delinquency of the judiciary in monitoring of the OBC group. This is the fundamental issue. Until now the idea of India jurisprudence adopts a ‘rational basis’ standard to examine classification of groups. In simple words, it defers to the political players to select their groups for special treatment. The jurisprudence also invidiously discriminates between the INSIDE and the OUTSIDE groups. For example – in the Jat 2015 case the honorable court put a very high evidence bar on entry of outside groups into the inside. But those already on the inside are permanently immune from that same level of scrutiny. I recall blogging the KGB court with much bombast in 2007 Thakur case announced a full monitoring of the OBC group in 5 years or 10 years. Both the deadlines have come and gone.

- There are some mechanics issues with the system that demand a separate quota for unreserved. An example is the Roster System followed in promotions. It can be mathematically proven that the roster system and the consequential seniority issue can wipe out the unreserved , with enough turns of the roster. The effects will be apparent as time goes by and the senior tier retires.

Seen in isolation, the EWS quota is absurd. The full picture demands you have to account for the Idea of India jurisprudence that defers to the political forces to reward the very groups that sustain them. I believe this has major effects – groups like Marathas , Kapus, Patels cannot wait forever biding their time for #IOI jurisprudence to develop a spine , i.e develop a first principles position. The spine.

Q4. What a joke – how is the the 8 Lakhs limit economically weaker ?

In a Dravidian Kazhakam meeting last month, Prof Suba Veerapandian drove home this point to a gullible Tamil audience who cheered – rather mindlessly. He called out “Not only was the EWS quota anti-social justice but the limit of 8Lakhs was a joke.” (paraphrased)

There is some truth to it, how can you call someone who earns 5 times the per-capita as EWS? But the issue is not that simple when you apply a core type analysis. This is going to be really counter intuitive . Follow me, you will get the A-Ha! moment.

Will a 3 lakhs limit be better?

I am going to directly use Tamil Brahmin as a stand-in example to expressly answer the Dravidians. Stay with me.

Say the EWS quota were to be restricted to poor tamil brahmins who earn less than 3Lakh instead of the 8Lakhs. Would the DK then support it? The lower level cadre will say yes. But the upper levels will be quite alarmed. Why? because you have to see all quotas as a state allocation program.

Every state program has a “social-impact-index” independent of the ecosystems efforts to hide it. The poor among the BC , SC, do not get any benefits because the targeting is at the elite layer. The dravidian argument is that targeting the elite benefits the poor via trickledown. A highly specious claim, but be that as it may. To this scheme lets assign a social-impact-index=50, if you introduce a program for poor tamil brahmins at 3L, then you directly and highly efficiently target the poor rather than the elite trickledown, so that has a social-impact-index=100.

Therefore instituting a 3Lakhs cutoff for poor tamil brahmins and having no such program for poor among BC/SC/MBC means the state gives a high-social-impact product to the brahmins and a low-social-impact to the non-brahmins. On the ground this will manifest as a son of a tamizh brahmin dosa master cook getting the benefit directly but the son of a non brahmin parota master getting nothing and waiting for trickle down from the hotel owner.

This kind of anomaly will expose and decimate an elite targeting movement like Dravidianism. Clearly Prof Suba Veerapandian has not really thought it through. A hypothetical smarter BJP would counter this by reducing the income cutoff to 3L and then see how they respond.

Even a 8L cutoff in TN suffers from the issue , because BC/SC/ST students whose parents make less than 8L get no special treatment. But the effects will be more muted than a much lower cutoff. I am willing to bet, while hearing the case the Supreme Court will get caught up in this paradox and miss the nuance completely. They simply have not evolved the bedrock principles to analyze these things beyond superficial.

See this video of Prof Suba Veerapandian delivered to a packed Tamil audience.

Watch the cunning deception here : on one hand they say “Reservation is not a poverty reduction scheme” while justifying the targeting of the elite. But when cornered on that , they switch to economic grounds. In the above clip he says in Tamil ( மாடு மேய்கிறவர்கள் , கூலி தொழிலாளிகள், தன முதுகில் மூட்டை சுமந்து வேர்வை சிந்துபவர்கள் , துப்புரவு தொழிலாளிகள் – இவர்கள் எல்லாம் ஏழை இல்லயாம் , அனால் மாதம் 64கே சம்பாதிக்கறவர்கள் ஏழையாம் ) in English – (those who herd cows, daily wage coolies, those who lift gunny bags on back for a living, those sanitation workers, they are not poor. But Modi govt has announced that 65K per month is EWS.)

The gullible and low info Tamil crowd laps it up and no one on stage has a proper response. Dravidians should not use the gunny back lifter to justify their stand, they should use doctors, professors, and govt servants in defence of their stand.

Q5. Why is this such a hot issue in Tamilnadu alone ? all states notified

If you are a non Tamil, you can skip this section.

Most states across the country , Assam, MP, UP, even Momata’s WB, GJ, MH, have notified the quota or are will notify it next year. What is surprising is even the Dravidian states – Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Kerala , Telangana are implementing in various forms. So the question for Prof Suba Vee is – how come your Racial dravidian brothers have no problem with this?

Upon deeper analysis you find the root of Dravidian exceptionalism lies in the numbers. The annual MBBS admission numbers provide a rare peek into the statistics. I monitored the last 5 years and found that only between 4.5 to 7% of the candidate population is classified as Unreserved , i.e. Forward Caste. The similar number for Andhra are roughly 42%, Telangana 47%, Kerala 40%, Karnataka 38 to 42%.

We can have many conversations about social justice and dravidians but the elephant in the room will always be the following. The very real possibility that Dravidian movement at its core is not interested in social justice at all but in outright discrimination against one group. As one judge remarked , if a state scheme gives privileged treatment to 94% of the population then you have crossed the line into reverse discrimination. Unless of course you have data to show that the 6% dominates to the extent that justifies it.

I used to wonder why Dravidian intellectuals Aasi K. Veeramani, Pera Suba Veerapandian, and Dr Pazha Karuppiah never proposed an easy truce settlement. You do not have to like the tamizhbrahmins – to say ‘here take your share and fo’ this truce will leave the Suba Vees in peace to build their glorious Dravidian society. In one stroke you will silence all criticisms of the reservation. After all, Dravidians themselves gave 3.5% to Christians and Moslems. If you do 69% , why not do 72% and in exchange buy complete peace and immunity?

One is helpless but to draw the correct inference from this strident stand. If Dravidians concede the 3% , then they also concede their primary raison-d-etre , which is anti-tamil-brahminism. Their top tier knows that if they give the share, then the thundering speeches of intellectuals like Pala Karuppiah will sound hollow and toothless.

A second , more dangerous issue, is if Tamil Brahmin get the 3%, then the focus will turn inwards into the vastly disparate Dravidian group itself and demands from other castes to get a look into their share. That is always the existential danger in TN politics. Never look under the kimono.

Q5. Is the 10% quota for EWS a ‘slow poison’ for social justice

Stalin thundered recently

Assailing the 10% quota for EWS, Mr. Stalin said it was not only against the Constitution but also detrimental to social justice. Pointing out a report in The Hindu that said that only 1% of the top teaching posts in Central universities were occupied by OBCs, he said while the AIADMK harped on former Chief Minister Jayalalithaa’s efforts in implementing the 69% reservation, the 10% quota would make her achievements go in vain. The present system of leaving 31% seats for open competition candidates was functioning well and there was no need for implementing 10% reservation for EWS, Mr. Stalin argued and charged that the Centre’s proposal was “slow poison” for social justice in Tamil Nadu.

Source : The Hindu

Is giving 10% quota for FC a slow poison for social justice? Well, as per the Justice Party leaders including Mr EV Ramaswamy himself – a complete communal quota is the correct model for social justice. Even Prof Suba Veerapandian announced recently that the ideal scheme is “Every community gets it share” . Their own founders notified the Madras Communal G.O and eventually lead to the Champakam Dorairajan case and the very 1st constitution amendment.

Regarding the statistic that 1% of teaching job in central universities is occupied by OBC, it may true or not. It is not relevant at all. If DMK wants this level of data, then it should constitute a proper Backward Classes commission as instructed by the Supreme Court and demand a study the beneficiaries. If there is backlog and scamming in Central Univ BC teaching spots, that must be fixed. No argument. there.

Q7. What do the results show in TN

The 2019 NEET results expose one of the foundation lies of the Dravidians. That non brahmin are somehow inferior in academics. Year after year, I have proven that brilliant students and toppers come from the non-brahmin tamil community. EVen in 2009, 8 of the top 10 rankers are BC. Merit is NOT the preserve of one group. You cannot allow such a patently bogus and casteist stereotype as the cornerstone of your ideology.

Q8. Any solutions for TN ?

This EWS is not an issue for rest of India or even the Dravidian blood states KL/KA/AP. A solution can be a lower 4% and a lower limit of 3L, but see my previous point for the hazard in this.

In Tamilnadu, I feel this is an existential issue to the hardline anti-brahmin elements within the Dravidian group, while the social justice focused types might accede to it. The hardline is always represented by the elite castes who do not have a social justice vision. For these types – conceding the quota has the effect of immunizing against their rhetorics. Of its most vulgar, virulent, and uncompromising elements like Dr Pala Karuppiah. Their speeches will have no sting left. Like rabid canines barking at passing vehicles as they get left behind in the march of civilization.

/jh

Explaining the 93rd Amendment to the BJP

Recently a former social media volunteer and now an office bearer in the BJP govt at the Centre made the following comment in response to my #RTE tweets.

Let us not blame the Congress, the Right to Education Act as passed by the UPA did not exempt minority institutions – the Supreme Court did. So this is the court’s fault and not the Congress partys.

(from Twitter – dont recall exact words)

Another variant of this I’ve seen with very senior BJP members is “Please do not attack RTE on sectarian grounds, the law is not the problem the Constitution of India is” . The same sentiment is also expressed sometimes as “.. that minority thing is a constitutional issue. Lets not go there – lets talk about teacher training instead“.

This mindset is disturbing on many levels and belies an understanding of the issues. Lets take a deeper look at the 93rd Amendment, history of Article 15, and the Right to Education Act.

OBC Quota in Central Institutes used to piggyback

Twin issues that appear to be related but arent. The 93rd Amendment and the OBC Quota. Let us see how the Congress government brilliantly intertwined the two.

I have already written an article titled “A Brief History of the 93rd Constitutional Amendment” where I’ve covered some of the landmark Supreme Court judgments that made Hindu educational institutions gain equal legal status as those run by minorities. I want to pick up where I left off. Lets cut to one of the major efforts of the UPA-1 government, one that took 4 years of extreme effort of Congress to accomplish. The 27% Quota for OBC (Other Backward Castes) in Central Educational Institutions like IIT/IIM/AIIMS/HCU etc.

First, as soon as UPA-1 stormed into power they realized that TMA Pai v State of Karnataka (2002) had to be overturned. The final push came in Aug 2005 when the Supreme Court in a 7-judge bench P.A Inamdar & Ors vs State of Maharashtra affirmed the essential parity in Education between Hindus and Minorities.

Secondly, the OBC quota issue was raked up and had the vociferous support of all the parties. Even within the BJP the OBC bloc seems to have supported the quota. Now here is how the two were mixed up. The UPA used the popular sentiment for OBC quota to piggyback the 93rd Amendment. It is not at all clear to me that you even needed an amendment to provide the OBC Quota. To explore this further you need a little bit of info about the Article 15 of our constitution.

History of Article 15.

Article 15 – the simplest of articles in all countries – had the most harrowing journey in India. The simple diktat was “thou shall not discriminate on basis of ..” The original article read like this

15. Prohibition of discrimination on grounds of religion, race, caste, sex or place of birth.-

15 (1) The State shall not discriminate against any citizen on grounds only of religion, race, caste, sex, place of birth or any of them.

15 (2) No citizen shall, on grounds only of religion, race, caste, sex, place of birth or any of them, be subject to any disability, liability, restriction or condition with regard to

(a) access to shops, public restaurants, hotels and places of public entertainment; or

(b) the use of wells, tanks, bathing ghats, roads and places of public resort maintained wholly or partly out of State funds or dedicated to the use of the general public.15(3) Nothing in this article shall prevent the State from making any special provision for women and children.

No sooner did the constituent assembly finish its job and the British has left our shores, than this article was subject to mutilation. Tamilnadu’s communal quota in college admissions was cancelled by a unanimous decision of the Madras High Court and then a Full 7 judges of the Supreme Court in State of Madras vs Champakam Dorairajan (1951) . Even before the First Lok Sabha had met – Jawaharlal Nehru and others who had participated in the Constitution making just a few months earlier overturned the Supreme Court’s decision and passed the First Amendment.

The First Amendment added a new clause (4) to Article 15 that read.

“15 (4) Nothing in this article or in clause (2) of article 29 shall prevent the State from making any special provision for the advancement of any socially and educationally backward classes of citizens or for the Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes.”.

Most of the states have been providing quotas to OBCs happily under the cover of Article 15(4) even though it does not specifically mention education. There is no reason why the UPA cant provide the OBC quota in Central Educational Institutions under this same non-obstante clause. But this was presented as an imperative and with overwhelming support of the OBC bloc and JDU deserting the NDA at the last minute the 93rd Amendment was passed.

The 93rd Amendment (at that time known as the 104th Constitution Amendment Bill) added a new clause (5) to Article 15 that read.

“15 (5) Nothing in this article or in sub-clause (g) of clause (1) of article 19 shall prevent the State from making any special provision, by law, for the advancement of any socially and educationally backward classes of citizens or for the Scheduled Castes or the Scheduled Tribes in so far as such special provisions relate to their admission to educational institutions including private educational institutions, whether aided or unaided by the State, other than the minority educational institutions referred to in clause (1) of article 30.”

Pay attention to the emphasized text to deduce the real intention of the 93rd Amendment. It had nothing to do with the OBC quota at all but everything to do with restoring the minority advantage that TMA-Pai and finally P.A Inamdar had leveled out. Specifically :

- The new Art 15(5) was to abrogate Art 19(1)(g) : By this I mean – Art 19(1)(g) (‘right to carry out an occupation’) which was used by TMA Pai to provide parity to Hindus was rendered waste as far as education was concerned.

- Art 30(1) was to be a non-obstante for the new Art 15 (5) : In other words : nothing in Art 15(5) shall apply to minorities involved in education field.

- Art 15(5) singular purpose appears to be to drive a wedge and elevate Art 30(1) “the minority” and completely abrogate Art 19(1)(g) “the non minority”.

After so many years of observing Indian political economy, I now think that the non-Congress parties are simply not intellectually equipped to see through these things. In any event , the 93rd Amendment passes and becomes an “enabling amendment”. So you may ask “what is an enabling amendment ?”. What was it supposed to “enable” ?

It enabled the grand confiscation that was still to come as the Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act 2009. Also known as RTE.

The Enabling Amendment

This is a curious creature I now know is uniquely Indian. Essentially the court strikes down something as ultra vires (outside powers) of the constitution ; then the politicians go and change the constitution itself to give it that elusive power. Now when the amendment itself is challenged the bar is suddenly very high. The court has to use the ill defined “Basic structure” test. ( Side Note : Justice Dalveer Bhandari thought that the 93rd Amendment was against the Basic structure even without the minority exemption. Luckily for UPA he wasnt around the court much longer)

Once again worth repeating what the Enabling Amendment contained and why the court had no role to harmonize :

- Explicitly exempted minorities in the amendment itself. Rather than depend on the court to harmonize with the protection already in Art 30. This ruled out some harmonizing with Art 30 – such as forcing minorities to admit own religion EWS or to force them to use lotteries.

- Explicitly abrogated Art 19(1)(g) protection to Hindus (non minority) in the amendment itself. Rather than depend on the court to harmonize (for example by severing provisions impinging on full refund & autonomy in selection etc).

Now you can say that this was all just a happy co-incidence.

I was also wondering if the Congress really lucked out and that the amendment was phrased by accident. Look at what Manish Tiwari of the Congress wrote recently about the Indira Sawhney judgment

On November 16, 1992, the Supreme Court by a majority of 6:3 upheld 27 per cent reservation for the socially and educationally backward classes (read Other Backward Castes) provided by the V.P. Singh government while striking down the 10 per cent reservation for economically backward sections of society provided by the successor Narasimha Rao government. ..

Why did 10 per cent reservation for the economically backward cutting across communities not covered by the existing quota architecture not find favour with the Supreme Court? For the simple reason that the Rao government was only paying lip service to the cause of economic reservation.

Kesri ensured that despite the amendment to the earlier Office Memorandum, no economic criterion was ever evolved and presented to the Supreme Court and no enabling constitutional amendment was carried out.

Source DC : State of the Union : Regression for Progression by Manish Tiwari

So there you go. The Congress lawyers have been through this. They knew very well from the ill fated econ quota in the Mandal saga that without an enabling amendment the laws were simply going to be struck down.

This was what they used in the Right to Education Act.

RTE Act as passed did not exempt minorities

As passed by the Parliament the Right to Education Act did not exempt minority institutions. But even I could smell the disaster from my little perch in nowhere land [ “RTE how well thought out is this – Dec 2009” ].

UPA-2 HRD Minister Mr Kapil Sibal met a lot of minority community leaders who were protesting the Right to Education Act. I dont know exactly what transpired. In any case, in no time the RTE was challenged in the Supreme Court and the unaided minority schools got exempted from the law in a 2-1 Decision in Society of Unaided Private Schools Rajasthan vs Union of India (Apr 2012) Why?

Because of two things :

- The enabling amendment did not just keep quiet on minorities but explicitly exempted them – it was a foregone conclusion that the court would strike it down for them. Leaving only the Hindus (non minority) wide open

- The court erred in not using the so called “Doctrine of Severability”. In short this doctrine means that if you chop off too much from a given statute – what is left does not make sense (i.e. is an absurd outcome). I guess only lawyers acquainted with the Lutyens and Supreme Court circuit at a very close level can explain why this happened. For an excellent analysis of this read “RTE Analysis : A question of severability“

Further down the road in May 2014 ; a 5-0 decision in Pramati Edu Society vs Union of India further pushed the RTE and exempted even the aided minority schools from the entire provisions of the act. ( See pp 26 of judgment that uses the exemption in enabling amendment to waive the law)

So to cut a long story short : The so called “Enabling Amendment” allowed the government to pass an ostensibly secular Act and the minorities can get out of it on a mere “facial challenge” – i.e. easy work.

If my friend got this far – I am sure he would realize what we are dealing with here. The 93rd Amendment cannot be divorced from RTE. The latter is built on the former.

/ jh

Jat quota issue and the relative backwardness test

About 10 railway stations are burnt, 60 trains stopped, schools, police stations burnt, a private armory looted, curfew in 6 towns in Haryana, 8 dead, police, paramilitary, and Army called in to douse the flames. This is a snapshot of what is happening in the immediate vicinity of the National Capital Territory of Delhi for the past 2 days.

Why is this happening ? A lot of simplistic comment is floating around the internet and in media op-eds. Almost all of them blaming the Jats for indulging in this kind of violence. Some of the commentators frown on the entire quota system and urge the Jats to be magnanimous and not seek the forbidden fruit. They dont realize that the quota system is a central part of the social and political system of organization known as the “Idea of India”. So its kind of odd that you’d call on a large group to sit outside the main political order. In reality, these commentators don’t want to be bothered with analysis of these issues and would wish the problem would go away.

In this post, I will try to go to the root of the problem in as simple a language I can attempt. From a completely different angle. Hopefully at the end of this you will see that the real culprits may not be the Jats at all

Brief history

Here is a brief recap of the Jat quota issue just enough for you to follow the rest of this post. India provides explicit quotas to various groups of communities. The keyword is ‘group’ not ‘communities’. The largest such group is known as OBC – Other Backward Classes. Various discrete communities / castes are included in these groups, they are maintained as “Lists”. These Lists are maintained for each state – called State Lists, and a single list at the central level called a Central List. The idea is that for Central Govt slots (jobs, college seats, scholarships, central police forces, and a host of other opportunities) they would use the Central list and for State Govt slots they would use the State list. Now you may ask – ‘Well that is weird, how can a caste be in one list and not be in the other“. Hold that question for a moment, you will realize even such simple questions cant elicit an answer.

Jats are in the state lists in a number of states like Rajasthan, Haryana, Delhi, UP, Bihar, HP, Uttarakhand and Gujarat. But they were not in the Central list. This meant they could only access the open category central govt slots and not access the large chunk of slots reserved exclusively for those in the Central OBC List. Due to sustained pressure and rioting. The UPA Govt included them in the Central List in March 2014. Not surprisingly, the other castes already in the central list would not have a new competitor and decide to fight the inclusion of Jats. Keep in mind that within each group (SC/ ST/ OBC) there is open competition among all castes in that list. Welfare associations representing the castes already in the Central List took it to the Supreme Court in a case called Ram Singh and Ors vs Union of India. A two judge bench of the Supreme Court struck down the UPA Govts notification and thus denied entry of Jats into the Central List. As things stand now, the quest is to balance the Jat aspirations with the persuasive qualities of the judgment. That is the brief recap of the genesis and current position of the Jat quota. Notice that I have not paid much attention to various govt bodies like NCBC and ICSSR etc. I believe these institutions are supposed to provide a check but the core rationale behind these institutions are missing.

For that you have to go a bit deeper.

Ram Singh & Ors v Union of India (link)

First thing to notice is the name of the case. It is Ram Singh & Ors vs Union of India. This is a PIL case initiated by an umbrella group called the “OBC Reservation Raksha Samiti” presumably the gentleman Ram Singh was one of the petitioners.. The word “Raksha” in Hindi means protection. Protection against outsiders barging in to the group. This case is therefore the result of inside group resisting the outside group. This may not seem important but forms the core of the issue as we will see.

So how does a caste get into the OBC list ? To answer that you have to refine that question. To get into a state OBC list you can petition the state govt and based on various considerations they may or may not grant that status. This is in fact where the major part of political effort is spent behind the scenes. For the procedure to get on to the Central list you have to go back to the 90’s. When reservation in Central Govt jobs was introduced as part of adopting the Mandal Commission recommendations the act was challenged. In an epic case called “Indira Sawhney & Ors vs Union of India“. The court upheld the quota and directed the govt to set up a body to examine claims of inclusion and exclusion. This body came to be known as the NCBC – National Commission for Backward Classes. The idea is that there would be robust tribunal that would scrutinize the entire program and could examine such claims with great authority. That turned out to be a disaster. The NCBC has not excluded a single group from the list nor has published any break up of utilization of each component. The entire exercise has a fatal flaw. The absence of ground rules. The lack of a single process or tests or even principles. The inability to state the conditions for initial entry into the list and whether the same process would apply to new entrants.

On paper, the recommendation of NCBC is supposed to be binding on the govt. But the NCBC itself isnt doing its job because of lack of ground rules. See how everything is linked back to the original anomaly? The entire chain is based on an absurd premise that you can create these compact lists in a nation of thousands of claimants. Most of us can hold our nose at this and pretend that nothing is wrong. Until a dominant and organized group like the Jats decide to challenge this scheme of things. They demand answers, no answers, then they want in by force. If that is what it takes. The Gujjars, the Vanniars, have all shown the way. For those parroting the “Constitutional Method” let me give you the reality check. A constitutional method requires simple ground rules (first principles) that stand alone. It never works when a court seeks to resolve conflicts between two groups. For that you need a conflict. And that is what the Jats are giving you.

Back to the Jat issue. In 2013, the Congress govt asked the NCBC for an opinion they said ‘no way’ without any convincing data. The Govt decided to go ahead and announce the inclusion of Jats anyway. Now this is the state of affairs as the case lands in the lap of a 2-judge bench of Justice Rohinton Nariman and Justice Ranjan Gogoi.

The judgment examines a lot of issues – particularly the powers of NCBC, the method used by ICSSR (the social agency which conducted a study), and some available data. They ruled against inclusion of Jats in the list on the following reasoning.

The perception of a self-proclaimed socially backward class of citizens or even the perception of the “advanced classes” as to the social status of the “less fortunates” cannot continue to be a constitutionally permissible yardstick for determination of backwardness, both in the context of Articles 15(4) and 16(4) of the Constitution. Neither can any longer backwardness be a matter of determination on the basis of mathematical formulae evolved by taking into account social, economic and educational indicators. Determination of backwardness must also cease to be relative; possible wrong inclusions cannot be the basis for further inclusions but the gates would be opened only to permit entry of the most distressed. Any other inclusion would be a serious abdication of the constitutional duty of the State. Judged by the aforesaid standards we must hold that inclusion of the politically organized classes (such as Jats) in the list of backward classes mainly, if not solely, on the basis that on same parameters other groups who have fared better have been so included cannot be affirmed.

pp 55. Ram Singh & Ors vs UOI

Put simply, what the bench is saying is. “The party is over folks, you cant get in merely because others have got in and they may be better positioned than you“. This is akin to pulling up the ladder after a certain number of groups have acquired the ‘inside’ status. Do we really think a large organized community like Jats (or Marathas or Kapus) will accept this line of reasoning ?

The judgment went on to say that it prefers discovery of new backward classes like the Transgenders who cut across castes. This part of the judgment was celebrated in the media. I fail to see why Transgenders should be given any quota. Accommodation yes, quota no.

Equal or separate processes

In my view, the judgment is fatally flawed on the following point “Determination of backwardness must also cease to be relative; possible wrong inclusions cannot be the basis for further inclusions” I would go a step further and state that the protests currently happening in Haryana turn on the moral unacceptability of this logic.

The judgment actually does a remarkable job summarizing the relative positions of Jats, Ahirs, Yadavs, and Kurmis. Reading the initial parts of the judgment you get the feeling like they are finally about to take the bull by the horns.. consider these factoids.

Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand, in the enrolment in higher and technical education, Jats lag behind Ahirs/Yadav

26 (out of 90) MLAs belonging to the Jat community and 4 Members of Parliament (out of 15), (Is this a factor ?)

Kurmis have 11.2% in professional education. Share of Jats is only.0.3% that is way below the share of Ahir and Kurmi shares (UP)

Among the Jats, 7.5% households have at least one member who is graduate, which is lower than the Ahir and Charan (RJ)

Jats with composite score of 1.17 are behind Gujars (1.34) and Ahirs (1.22). On net social standing, the composite score of Jats is 17.24, which is significantly lower than the Gujars (27.14) and Ahirs (19.85). On composite economic score, score of Jats is 16.55, lower than Gujars (19.38) but higher than the Ahirs (14.86). (Delhi)

After collating all this relative information, the judgment completely disappoints.The honorable judges dismiss the comparative data completely as of no relevance.

The question framed should not have been whether the proper procedure was followed in declaring Jats backward. Whether the NCBC rejection was binding and surrounding issues.

The question in my view should have been framed as an Article 14 issue – as an ‘equal protection’ case.

14. Equality before law The State shall not deny to any person equality before the law or the equal protection of the laws within the territory of India Prohibition of discrimination on grounds of religion, race, caste, sex or place of birth

The above sentence is the much mutilated Article 14 (equality) clause in the Indian constitution. Now I fully understand that the Indian constitution has juxtaposed “Idea of India” doctrine as an exception to “Rule of Law“. Remember that the central proposition in Rule of Law is uniform application and that the central feature of Idea of India is to create separate processes for groups.

Even if this is the case, the equal protection clause must guarantee that every community has the same process to get into the exception category. I repeat that – its not that you cant pick out groups for separate treatment but the process used to pick out groups for such treatment must be uniform.

Now turn to the facts of the OBC lists – the Idea of India jurisprudence has split the population into “Inside groups” (those already included in the list) and “Outside groups” those wanting to get into the list. The biggest problem is that those who are already inside did not go through the same process of measurement that the outsiders are being subject to. This is a gigantic anomaly that cant be brushed aside. This is especially important in a ‘game of spoils’ where there is no stigma to call your self anything as long as there are special and exclusive goods to be had.

Once you cast (no pun) the question as one of equal protection – it is clear that the Jats are being asked to come through a very highly fortified front door while there are others who are inside on much looser criteria through the back door. Also the revisions to the lists are not happening even in boundary conditions like Tamilnadu. This only means that inside group members seem to be permanently immune from scrutiny and even quantifiable relative data to outside groups now will not be accepted.

A relative test

My view is exactly 180-degrees from the judgment. The inclusion and exclusion issues must be purely relative. There cannot be any absolute measure of backwardness because remember that within the OBC group there is a pure meritocracy. The “List” ought to be the central subject of all litigation and the main job of the statutory body and the judicial review process is to preserve the integrity of the list. All it should take for Group-A to declare the entire list invalid is to show that there is atleast one Inside Group that is better off than atleast one Outside Group. At the state level, things are totally absurd. I have proved that in Tamilnadu the situation is out of control. There are no students from the open category getting through PG Medical Tamilnadu Seats in top colleges.

It is also important to not expand the domain where the quotas can be asserted. Especially dangerous is local body quota which distorts the entire democratic process itself. Another live wire is sectarian spending such as group wise scholarships, special schools and vocational training only for some groups, special financing, and such like.

Careful of that Pandora’s box

One of the dismaying phenom in India is the following : The establishment try some mad-scientist experiments with the Rule of Law (which evolved in the west as an outcome of centuries of bloodshed) , the experiment doesnt work, so they drop some assumptions and open an entirely new can of worms. In the previous regime, if there were 8 people who could wrap their heads around the issues, when you drop down a level and open a can of worms only 4 can handle it. This has been going on for too long. Now no one seems to have control of the situation. Some new can of worms ready to be opened are.

Can all states be like Tamilnadu ? Declare 90-95% as backward ?

Can all groups (castes/religions) be given a pro-rata allocation ? Remember this was the issue in Champakam Dorairajan vs Union of India that prompted the first amendment. Stunning we want to go back to the Communal G.O in Madras Presidency after 70 years of Independence.

In any invidious law ; the people always measure their impact with respect to other people. If a Jat aspirant loses a bank job, it is someone else who gets it. This is the source of the tension and only a relative test can soothe it.

Truly a crisis situation. Only next to the rot in our education laws.

SG Punalekar vs Union of India – Bombay HC judgment upholding Minority-only scholarships

srk 1 wp-84-08-final

IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUDICATURE AT BOMBAY

ORDINARY ORIGINAL CIVIL JURISDICTION

WRIT PETITION NO.84 OF 2008

1. Sanjiv Gajanan Punalekar,

Indian Adult aged 42 years, a

practicing advocate, residing at

Flat No.25, Malkani Mahal,

261, Annie Besant Road,

Worli, Mumbai-400 030. … Petitioner

Versus

1. Union of India, Ministry of Minority

Affairs, through Department of Law,

Ayakar Bhavan, Mumbai and others.

2. State of Maharashtra

through Government Pleader.

3. Union of India,

Ministry of Human Resources Department,

Shastri Bhawan,

Dr. Rajendra Prasad Marg,

New Delhi-110 001. … Respondents

Mr. Ashish Naik for the petitioner.

Mr. D.J. Khambatta, Additional Solicitor General with Mr. Rui Rodrigues and Mr. Gulam Ankhad and Nirmal R. Prajapati i/by Dr. T.C. Kaushik for respondent No.1.

Mr. D.A.Nalawade, Government Pleader for State. srk 2 wp-84-08-final

ALONGWITH

APPELLATE SIDE

PUBLIC INTEREST LITIGATION NO.254 OF 2009

Smt. Jyotika Wale,

Age 59, Occ. Social Worker,

R/at L/2, 902, Hariganga, Oppo.

RTO, Yerawada, Pune-6. … Petitioner

Versus

1. Union of India, Ministry of Minority

Affairs, New Delhi .

2. The State of Maharashtra,

Through the Secretary,

Department of Education,

Mantralaya, Mumbai,

Copy to be served on A.G.P. High Court,

Appellate Side, P.W.D. Building,

Mumbai-32. … Respondents

Mr. Aniruddha Rajput with Mr.P.G.Chavan and Mr. Mayur Khandeparkar for the petitioner.

Mr. D.J. Khambatta, Additional Solicitor General with Mr. Rui Rodrigues and Mr.Aditya Mehta and Mr. N.R.Prajapati for respondent No.1. Mr. Mayur Khandeparkar with Mr. Gandhar Raikar for applicant in C.A.No.63 of 2011.

Ms. Neha Palshikar-Bhide, `B’ Panel Counsel for State. srk 3 wp-84-08-final

CORAM : MOHIT S. SHAH, C.J. &

D.G. KARNIK, J.

Judgment reserved on 19th April, 2011

Judgment pronounced on 6th June, 2011

JUDGMENT (Per Chief Justice)

Since both these petitions purporting to be PILs raise common issues of law and facts, the petitions were heard together and are being disposed of by this common judgment.

Broad Controversy

2. PIL 84 of 2008 is filed by a practicing advocate who challenges the “Merit-cum-Means Scholarship Scheme for Students of Minority Communities” issued by the Government of India in the Ministry of Minority Affairs on 1st April, 2008 (Exhibit `A’ to the petition) on the ground that it discriminates against students belonging to the majority community only on the ground of religion. The petitioner has prayed that since the scheme is unconstitutional, it be cancelled.

srk 4 wp-84-08-final